Passenger ships: the key to low-carbon international travel?

Translation: Jean-Rémi Chareyre

There is no tiptoeing around the fact: in Iceland, the aviation industry is the elephant in the room when it comes to climate change mitigation. It is perplexing to observe that, while we have set ourselves a lofty goal of becoming fossil-fuel free by 2050 (before all other countries), we have at the same time been significantly increasing our imports of oil, mainly due to the growth of the aviation industry. Oil imports were more or less stable from 2000 to 2015, but the next few years saw an explosion in oil sales: from 784,000 tons in 2015 (the year the Paris agreement was signed) to 1,027,500 tons in 2018, or a 30% increase in only three years. Kerosene sales almost doubled during the same period and represented 40% of all oil imports by 2018.

This is not just a question of inbound tourism. Icelanders fly much more often than they used to. According to statistics from the Icelandic Tourist Board (Ferðamálastofa), only about 44% of Icelanders travelled abroad in 2009, but the proportion had increased to 80% in 2017. At the beginning of the same period, Icelanders took an average of 1.2 trips abroad per year. By the end of it the average was 3 trips per person per year.

The aviation industry would like to convince us that the problem will be solved with the advent of green fuels such as biofuels, e-fuels or liquefied hydrogen. Technically, there is no major hurdle to switching from oil to green fuels. The devil is in the details, that is, the scaling-up and the infrastructure. We simply will not be able to produce green fuels in sufficient quantities for the 20,000 passenger jets that fly across the globe every single day, in addition to all of the ships, trucks and other machinery which are also supposed to keep running thanks to a green fuel miracle. In order to satisfy current demand, we would need a gigantic amount of renewable energy, along with a plentiful supply of organic matter, which will simply not be available in sufficient quantities. Green passenger planes will therefore at best become the privilege of a small elite.

When oil empowered the plane

It is no coincidence the advent of air travel on the world stage was belated compared to land and sea transportation. Engineers had long dreamt of giving man the ability to fly like a bird. Among others, Leonardo da Vinci had the idea of designing a man-powered flying device with flapping wings, as this sketch of his reveals (ca. 1490):

But manpower proved too weak to propel such a device, which, unlike a ship or cart, needs to constantly fight against the force of gravity that pulls it down to the earth. It was not until the advent of the oil age that the plane could make its breakthrough. Shortly after the first oil field was discovered in Western Pennsylvania in 1859, American engineers started fiddling with it. By the end of the same century, the internal combustion engine had been invented and commercialised. The Wright brothers quickly picked up on this innovation and crafted the first airplane that could actually take off in 1903 (although this first plane only covered a modest distance of 260 meters). In other words, the plane was born with oil and will die with oil, at least as a cheap mode of transportation.

The reasons for this are to be found in oil’s exceptional qualities as an energy source. It has a comparatively high energy density (twice as many energy units per kilogram as coal and a hundred times more than gas). Its liquid form makes oil extraction, transportation and storage easy and cheap (unlike coal and gas), and oil is both an energy source and energy holder (unlike electricity, which cannot be stored except in battery form). Last but not least, oil has been ‒ so far ‒ available in almost infinite quantities.

And this is exactly what the plane needed to take off: an energy source that takes up as small a volume as possible, is as lightweight as possible, can flow freely towards the engine and is plentiful and cheap. But as we know, oil is a limited resource, which moreover leads to greenhouse gas emissions that we are determined to drastically reduce for climate reasons. Abundance of cheap oil will soon become a thing of the past, whether for political or natural reasons.

Plenty more fish in the sea

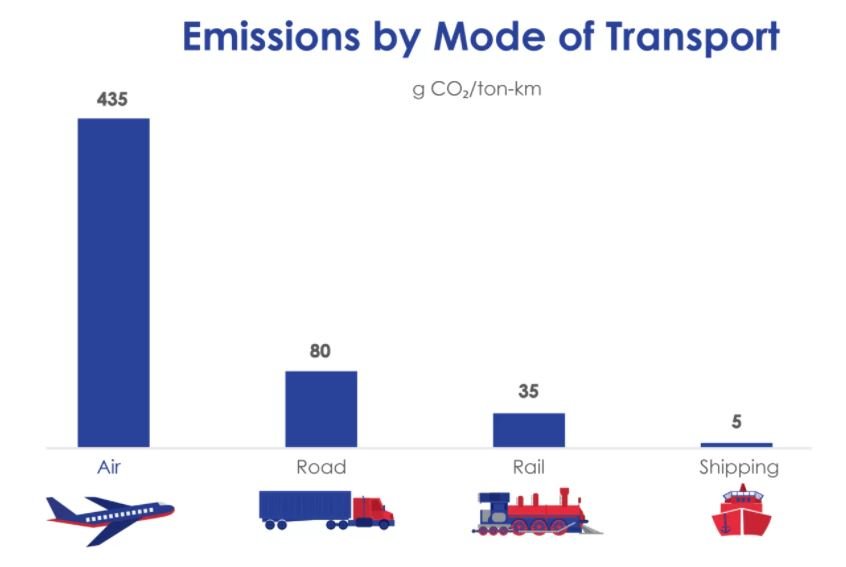

CO₂-emissions in freight transport. Source: International Marine Organization (IMO)

Fortunately, we have an alternative to air travel when it comes to intercontinental travel. Marine navigation is in fact a much older mode of transportation (at least 50,000 years old), and the reason again, has everything to do with energy. While air travel is the most energy-intensive mode of transportation (for gravity reasons), marine transport is the most energy-efficient, as a ship only needs to slide smoothly on the horizontal sea surface. Wind energy has a very low energy-density as compared to oil, and yet it proved sufficient for our ancestors to move passengers and trade goods between continents with the advent of sailing, thanks to the low-energy demands of marine transport. Modern ships are for the most part oil-powered, but are still much more energy-efficient than other means of transportation, both on land and in the air. For each ton of moved freight, a ship burns 10-20 times less fuel than a truck and a hundred times less fuel than a plane.

Before cheap plane tickets became the norm, most Icelanders travelled to Europe and America by sea via passenger ships such as Gullfoss, which sailed until 1972, after which competition from air travel led shipping companies to abandon passenger transportation.

The ship Gullfoss was used for passenger and freight transportation between Iceland and the mainland up to 1972.

Today, the Norröna ferry that sails from Seyðisfjörður in east Iceland to Hirtshals in Denmark is the only way to travel to and from Iceland by ship (the trip takes two days each way). But is Norröna an eco-friendly alternative to air travel? Yes, it can lead to significantly reduced emissions, but it depends on a few factors, and especially whether or not a car is involved. Marine transportation in general could become a much more climate-friendly travel option, provided there is both popular and political will to revive and promote it as a viable alternative.

The Norröna ferry, a Faroese ship that sails from Seyðisfjörður in the east of Iceland to Hirtshals in northern Denmark (with a stop in the Faroe Islands).

As mentioned above, freight transport by sea has a carbon footprint per ton/km a hundred times lower than air freight. But when it comes to passenger ships, the picture is a bit more complex. Passengers need more space than merchandise. Fuel consumption per passenger, along with associated emissions, are directly dependent on how efficiently space on the ship is allocated. In ferries which take only foot passengers and go short distances, the ship volume is used very efficiently and therefore emissions per passenger are almost ten times lower than flight emissions.

Emissions per passenger on cruise ships, however, can be much higher, and in some cases even higher than flight emissions. There are two reasons for this. The first one is the fact that on longer trips, passengers need more facilities, such as a sleeping cabin, a shower, and eating facilities. Flights are seldom so long as to require sleeping or shower facilities. On longer trips, therefore, a ship cannot hope to take as many passengers as a plane of the same size.

The other reason for this is that competition from air travel has forced shipping companies to change their business model. As ships could not compete on the basis of speed or price, they instead specialised in luxury. Exactly because ships are much more fuel-efficient than planes, it proved possible to “waste” a considerable share of the ship’s capacity on all kinds of frivolous services that plane passengers could never have dreamt about.

Queen Mary II

Queen Mary II could transport the whole Icelandic nation

Meet Queen Mary II (see picture), a passenger ship that sails between Europe and the U.S. She can take about 2,600 passengers, which is about five times the capacity of a Boeing 747. Queen Mary II features 15 restaurants and bars, 5 swimming pools, shops, a casino, a ballroom, a theatre, a planetarium and passenger suites with balconies, among others. In a Boeing 747, as a comparison, the average passenger has access to one seat and the facility looks something like this:

A ship’s volume is usually expressed in gross tons (GT). Queen Mary II has a volume of 150,000 gross tons. That’s about 58 gross tons per person. In contrast, a Boeing 747 has a volume a thousand times smaller than Queen Mary II (130 gross tons), but still takes about 500 passengers thanks to the sardine method, which makes only 0.26 gross tons per passenger. In other words, a passenger on board Queen Mary II has 220 times more available space than an air passenger. If we would stuff people in the Queen Mary II like we cram people together on a plane, the ship could transport more than 500.000 people – the whole Icelandic nation and some more! Not very practical, perhaps, but a good reminder of how wasteful of space modern cruise ships are, due to the aforementioned competition with planes. We can then turn the calculation around: if we wasted as much space on planes as we do on cruise ships, then a Boeing 747 could only transport about 3 passengers…

Queen Mary II, Titanic and Airbus A380. A size comparison. Source: lowtechmagazine.com

Norröna ferry could transport the whole Reykjavik population

Norröna is 37,000 gross tons and takes about 1,500 passengers. That is 25 gross tons per passenger, half as much as on Queen Mary II, but still a hundred times more space than on a plane. With the sardine method, she could take about 150,000 passengers, the rough equivalent of the whole population of Reykjavik. This is of course only true on paper. As mentioned above, sailing trips take longer, so passengers need more space. Still, space on Norröna could be used much more efficiently, as the ship features parking space for 800 cars, as well as 6 restaurants, a duty-free shop, hot tubs, a swimming pool, a fitness centre, a cinema, and a number of spacious suites with a living room, a minibar and bathrooms with both bathtub and shower. Just by switching cars for passengers, the number of passengers could be greatly increased.

Below is a picture of the ocean liner Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, which was built in 1897 and sailed between Europe and North-America. She had less than half the capacity of Norröna (14,350 gross tons), but could transport just as many passengers (1,500 of them, including 206 in first class), in spite of the fact that steam engines at the time were much bulkier than modern-day diesel engines and that the ship required some 500 crew members. This amounted to a volume of about 10 gross tons per passenger. With a similar space efficiency, Norröna could transport 4,000 passengers instead of 1,500, and each passenger would still have access to a space 40 times bigger than on an airplane.

The German ocean liner Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse sailed between Europe and North-America from 1897 to 1914.

Because of poor space efficiency, as well as the fact that Norröna was not designed with fuel efficiency as a priority, her CO₂-emissions per passenger are rather high compared to many other passenger ferries. Still, a foot passenger travelling on Norröna, if only using minimum service (access to a sleeping cabin, bathroom and cafeteria) has a carbon footprint of only 275 kg CO₂, while emissions from a flight between Keflavik and Copenhagen amount to 700 kg CO₂-equivalents, more than twice as much (source: Atmosfair flight-emissions calculator).

A more efficient passenger ship could easily reduce emissions down to about 165 kg-CO₂, a number four times lower than air travel emissions. Another option would be to make use of hybrid passenger/cargo-ships, which is exactly what was done with ships such as Gullfoss back in the day. This alternative would have the merit of ensuring a diversity of destinations, as freight ships already link Iceland to many different ports in Europe and elsewhere, with departures in or close to the capital area where most Icelanders live, such as Þorlákshöfn harbour or Reykjavik harbour.

A one-day ferry trip to Scotland?

We can take this further: a ferry trip from Þorlákshöfn to Northern Scotland (Thurso) is considerably shorter than to Denmark (1100 km instead of 1600 km), as well as a trip from Seyðisfjörður to Bergen in Norway (less than 1100 km). With a faster ferry (60 km/h instead of 40 km/h), the sailing time could be reduced to about 18 hours. Such a sailing time would mean that the ship would not need to provide accommodation and could therefore use space more efficiently. Ferries that take only foot passengers and go short distances, such as Staten Island Ferry in New York, need only provide about 0.5 gross tons per passenger. If we allow for 2 gross tons as an 18-hour journey calls for at least some catering service, we are left with a fuel consumption of only about 10 litres per passenger each way (31 kg CO₂). From Northern Scotland, passengers could then continue their trip via rail transport or by renting an electric vehicle, and could reach mainland Europe through the Channel Tunnel between the UK and France.

It should be added that the use of alternative fuels on ferries is a more realistic prospect than in air travel, as the volume and weight of the energy source is not as limiting on a ship. Maersk, one the largest shipping companies in the world, recently placed an order of 8 methanol-enabled vessels from the Korean manufacturer Hyundai Heavy Industries. The first delivery is due this very month (February 2024), so alternative fuels on ships are not just a distant utopia. A well-designed methanol-enabled ferry between Iceland and mainland Europe and America would lead to almost non-existent CO₂-emissions from international travel as compared to air travel, while methanol could be produced domestically with renewable energy, reducing the need for imports of energy products.

A ferry trip from Þorlákshöfn to Rotterdam would take two days, and from there, most of Icelanders’ favourite destinations would be within reach: 3 hours to Paris by rail, 4 hours to Frankfurt, 4 hours to London and 12 hours to Spain or Italy.

“But we live on an Island in the middle of the Atlantic!…”

Who hasn’t heard this complaint when high emissions from air travel are discussed in Iceland? A similar rhetoric is in fact used to justify sticking to a car-oriented transport system (“The weather here is so bad, public transportation and bicycling just don’t suit us!”) or rejecting a transition to electric mobility (“It’s so cold here, electric cars just won’t do the job!”). The Icelandic exceptionality comes in very handy when one wants to avoid changing unhealthy habits.

There is no question that ferry transit is much more time-consuming than air travel (a one-way trip with Norröna takes two days). “Others can travel by rail, bus or car, but we can’t since we live on an Island,” the sceptics will say. “We have no other choice but to fly!”

But then again, anybody can use their exceptionalism to justify the status-quo.

The Danes can say: “Our country is so flat that we can’t make use of hydropower and our windmills only work when the wind is blowing. We have no choice but to keep burning fossil fuels to produce our electricity!”

The Germans can say: “There are so many of us and we don’t have enough renewable energy, but we have a lot of coal, so we have no choice but to burn our coal!”

The British, Irish, Australians and others can say just like we do: “But we live on an island!”

The oil states of the Middle East can say: “But our economies are totally dependent on the fossil fuel industry. We have nothing else to sell. We have no choice but to continue exploiting fossil fuels.”

And the Americans can say: “But we have a huge country and a lousy rail system. We have no choice but to keep flying across our country as we see fit!”

And so on…

A resident of San Francisco who wishes to travel to Paris without taking a plane needs to drive for five days across the U.S., then sail for seven more days across the Atlantic. A total of 12 days at least (one way). A Portuguese citizen from Lisbon travelling to Paris by train needs at least 2 days, and 3 days to Berlin. A Polish citizen wishing to travel to Alicante needs 2-3 days and an Irish tourist dreaming of visiting Warsaw also needs 2-3 days. Everyone lives far away from somewhere…

It might also be sobering to remember that Iceland’s national hero, Jón Sigurðsson “the President,” who advocated fiercely for Iceland’s independence from Denmark, had to sail between Denmark and Iceland for many years while living in Denmark and attending parliamentary sessions at the Icelandic Alþingi. In those days, sailing ships were the only option, and the trip could take several weeks if winds were unfavourable. That didn’t prevent Jón Sigurðsson from being of greater service to his country than most of us will ever be…

Rather than focusing on reaching our destination as fast as possible, perhaps we should learn to enjoy the journey and reassess its meaning. “It’s not the destination, it’s the journey,” the philosopher said. Should we succeed, a revival of sea travel could prove to be a key to our emancipation from fossil fuels.

A music band on its way to the Folk Music Festival in Siglufjörður, performing on board the Norröna. The journalist had the luck to be on the same ferry trip as the orchestra in the summer of 2023 and immortalised the scene. Such a travel experience is something that air travel cannot provide…